Hello,

Welcome to the last 60-Second Psychology. Today’s post is about the importance of “purpose” for our health and longevity.

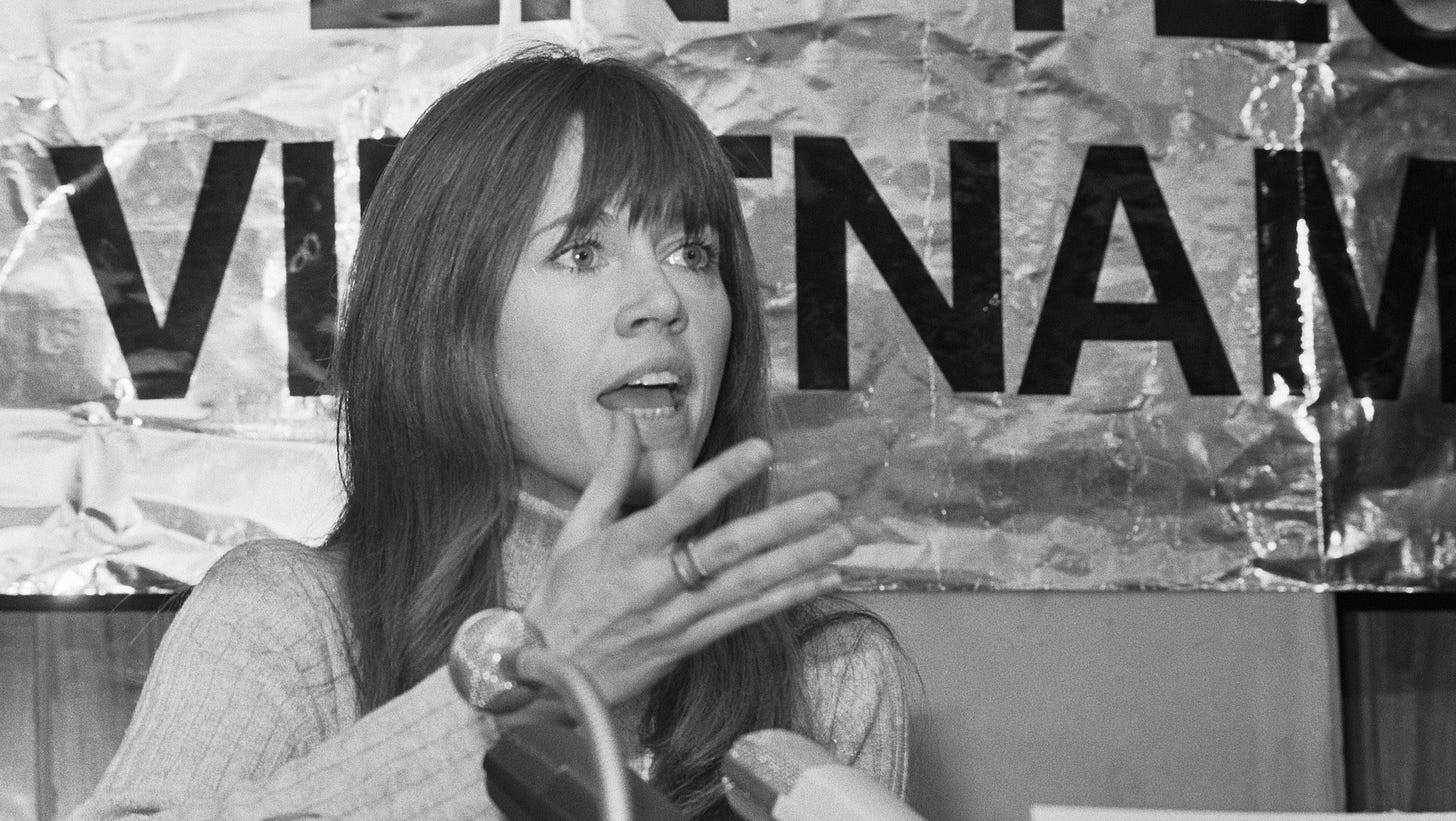

I was inspired by a recent interview with the actress Jane Fonda, who, at 87, describes feeling “younger than ever”. She argues that it’s her activism that has kept her youthful – from protesting the Vietnam War in the 60s to campaigning for climate justice.

“I’d led a pretty hedonistic and meaningless life and was unhappy in my younger years,” she told the Sydney Morning Herald. “I was very old at 20 and feel quite young at 87… For me, this mindset has a lot to do with a change in my attitude and living a purpose-driven life. When I got into protesting, I finally felt connected to something bigger than me.”

Fonda’s lived experience is borne out by a wealth of psychological research: people living a “purpose-driven life” are less susceptible to various illnesses and tend to show fewer signs of biological ageing.

Consider the results of the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) survey, which has followed more than 7000 people’s health and well-being since the mid-90s.

The scientists measured people’s purpose in life by asking them to rate the following statements on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree):

Some people wander aimlessly through life, but I am not one of them

I live life one day at a time and don’t really think about the future

I sometimes feel as if I’ve done all there is to do in life

Someone who strongly agrees with the first statement, and strongly disagrees with the second and third, is considered to exhibit greater purpose in life – and in the MIDUS survey, this predicted a lower risk of death in the following 14 years. “Even when selecting variables known to be relevant for understanding mortality risk in general and in this sample, we find that the benefits of purpose hold true,” the researchers conclude. Their later research suggests that purpose is more important than overall life satisfaction in predicting people’s physical health and longevity. Having a higher purpose in life can even render us more resilient to Alzheimer’s disease.

The physical benefits of a purpose-driven life are another manifestation of the mind-body connection. In the media, the influence of our mental state over our physiology is often presented as a mysterious, almost magical phenomenon – yet the potential pathways are extremely well established.

One is behavioural: people who feel greater meaning in their existence tend to stay more active into older age. (Jane Fonda is, of course, a wonderful example of this, having achieved acclaim in recent years for her roles in “The Newsroom” and “Grace and Frankie” while remaining committed to her political activism.)

The other is “psychobiological”, meaning that our mental state can have a direct influence over bodily processes. A greater sense of purpose appears to act as a shield against life’s slings and arrows, buffering our stress response when we are placed in challenging circumstances. It may be that when we have more meaning in our lives, our smaller everyday difficulties – a disagreement with our boss, say – seem to matter less; they are tiny frustrations in our grander narrative, and we feel empowered to deal with them. Our physiological response is less dramatic as a result.

If you struggle to feel much purpose in your existence, then the opposite is true: any perceived insult or frustration can threaten your fragile sense of self. You ruminate more and your body responds as if you’re in the throes of a crisis. It pours all its resources into dealing with a tiny irritant as if it were an existential danger.

The soothing power of purpose is evident in objective measures of people’s responses to difficult situations. In 2015, for instance, researchers put participants through the gruelling “Trier Social Stress Test”, which involves giving a presentation in front of a hostile audience, followed by some on-the-spot mental arithmetic. As you might expect, most people saw a spike in the “stress hormone” cortisol as they faced the judgemental faces. Those with a higher purpose in life recovered more quickly, however, whereas the people with less sense of purpose found it much harder to unwind afterwards.

Such differences could add up over time, and they seem to influence a range of biological systems – such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and inflammation – which can raise or lower our risk of many illnesses.

If you have been inspired by this research, there are plenty of ways to find your purpose. One useful exercise – courtesy of the University of California, Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center – is to think about your home, your community, and the world at large, and ask what you would change if you had a magic wand, and why. This helps us to identify the things that matter to us. You can then think about more concrete steps to achieve that change. You might also describe your ideal future and the ways it can align with your values, and reflect on the skills and actions you need to get there – a process called “life crafting”.

As I recently wrote for the Guardian, volunteering for a cause close to your heart is one of the best ways of prolonging your life for all of these reasons.

There are no right or wrong answers – it’s all about what is important to you. In the words of Jane Fonda: “Meaning can be doing well as a parent and raising your children. It can mean you've had a long and happy, profound, meaningful marriage or relationship. It can mean you've been kind all your life, it can mean any number of things. It doesn't have to mean I got rich or I got famous. I say that because I know a lot of people who are very rich and very famous and are miserable. It's all about going deeper.”

That’s all for this week! If you’ve enjoyed what you’ve read, you can support me by subscribing, sharing on your social media, or forwarding to a friend or family member.

David x